Last week, I decided I’m going to blog on occasion about stuff I like. It’s the censored version, in the sense that there won’t be a lot of swear-y bits, but at the same time it’s not the “I’m kissing butt” or the “I’m boasting about stuff I’ve worked on” variety. (If you haven’t met me, well…I’m very bad at those two things. HAH!) I think of this more as a window into my world: how I research, what I respond to, why I’m analyzing a piece of work. And in the effort of FULL disclosure, yes the links will likely be affiliate-related — but as I am not in the top tier of wealthy writers yet? So it goes.

PLUS, there’s a mega-ton of negativity out there, and really…less of that please. I mean, the entire reason why I wanted to write in genre is because it was fun — not because it felt like a chore or made me want to cry. Eesh. I’m also of the belief that if you (or I) love a work that much, it can be inspiring to apply the lessons learned to works of our own. Fans are the reason why I write, but the inspiration and the creativity I have doesn’t come out of thin air. It originates from everything around me: exhibits I go to, paintings I like — even books I consume or movies I inhale. Now, I might bore you with some of my comments about art or music in general, but I got the movies, comics, books, and games thing down.

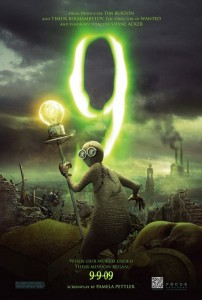

So today, I start with a movie that came out nine years ago: 9. There might be some spoilers here, but as it’s been NINE YEARS (she says, unironically), anything I say is in service to my overall point. This didn’t air nine minutes ago (*coughs* Game of Thrones)!

9 was a problematic movie for me when I first saw it, because it debuted with a lot of hype. When I go into a film, thinking it’s going to be the next what-have-you, then I have a certain set of expectations. Here, this wasn’t a Tim Burton film persay. Not in the same way I was already expecting, mind. Not in that Nightmare Before Christmas, Edward Scissorhands, Corpse Bride, or Beetlejuice operandus modi.

This movie begins with a short film by the creator, Shane Acker. The long form version originated out of a short form film by the same name, and you can find the original movie at the publisher’s website. 9 was groundbreaking animation at the time, and those visuals can dazzle me, but as I am married to story? There was a part of me that got suckered in to how great the film would be based on the chugga-chugga of the marketing train. When I saw it, I did enjoy it, but the experience was lessened by the hype.

Fast forward to today, where this movie was translated into Blu-Ray. I watched it again, this time paying attention to story. Animation has dramatically and significantly increased in production value since 2005, so the SFX and the hype are long gone for me. The story, to me, was about alchemy. That field, in an allegorical sense when applied to Western alchemists, as alchemy can be found in many different cultures, has elements of the Corn King or Christ myth. Sacrificing oneself to be resurrected later is a powerful theme, and here the scientist takes an action that allows that to happen.

In some ways, the main scientist’s character arc parallels Voldemort from the Harry Potter series. Here’s where they are different: the Scientist created something new and wondrous, and that science was co-opted by those who’d abuse it. Voldemort, on the other hand, has been presented as a boy/man unable to escape his fate, because of his lineage, his family. He never fights what he is, and he gets aggressive, manipulating other Hogwarts professors to split his soul *wink, wink* into Horcruxes.

That said, there are similarities between the two that I see. Voldemort’s pieces of soul both were and weren’t sentient. Contained in objects, each Horcrux had a kind of survival instinct. They chittered. And, when opened, the full brunt of his nasty soul came to bear. The journal, too, is possibly the best example of a sentient part of Voldemort’s soul, for when it was opened, a “shade” of his personality came out. How those shades manifested did vary somewhat, but they were all evil. In part, because the Horcruxes were made by committing acts of murder so that he could survive.

The Scientist in 9, for purposes of comparison, did something similar. Instead of acting on malice, his self-preservation was bound to his desire for redemption and to restore humanity to the world. When the Scientist split his soul, it was with the intent to save humanity. Each of his “Horcruxes” were rag dolls, with their own unique personalities, shapes, and — more importantly — motives. The conflict in 9 isn’t just an outward one, between the Matrix-like robots and the rag dolls, it’s also inward, too. The Scientist, in some respects, is fighting himself to survive.

What I liked about the film now, was the layers of storytelling present in the visual effects. Color, for example, is very important to this movie, as is texture and light and the shape of the rag doll’s eyes. There is a very specific attention to detail here, and I’m appreciative of that. I also really love the way that the alchemy was presented, because the whole point of this film is that the Scientist didn’t know if he was going to be successful. If you’ve seen the film, you’ll know where I’m coming from if you watch the ending again. Too, that ending scene? Hugely important. Even the shape used — which forms a pentagram — is important in the overall scheme of things. (e.g. Fibonacci sequence, five wounds for the Christ figure on the cross, etc.)

For all these reasons and more, I feel that 9 is one of those movies where it’s worth watching again. If you see it on the first time, sure there’s a story there. But watch it on the second or third time, and more details come to light. The main plot IS clear; it’s not reinforced over and over and over again like some movies today are. I will say that if you’re watching on the first time, though, put down your phones, tables, and instruments of distraction. It’s a movie with an interesting message, and I’m glad I’ve added it to my collection.